WHEN PAIN RULES YOUR WORLD

All about Pain

Why is it that sometimes pain doesn’t seem to want to go away? When I learned about pain way back in physiotherapy school it seemed fairly straight forward. I.e. you bruise your toe, a message goes to the brain and you feel pain in the toe. After a certain length of time the toe heals and the pain goes away. Pretty simple, right?

However, when I got out into the “real world” and started working with patients this simple formula fell apart. While many people did get better as expected, there was a group that did not. These people continued to have pain long after the initial period for healing had passed.

In cases where there is a well-defined reason for the pain, such as inflammatory arthritis or obvious joint or soft tissue disease, this can be understood, there is ongoing pathology. But what is going on when pain is still present weeks, months and even years after an injury has healed? Why doesn’t the pain stop? Am I still injured? Is the pain “real”?

Persistent Pain

Many people with persistent pain have gone to their doctor to find out what is wrong. Is there something that was missed or some serious problem that hasn’t been identified? They then have extensive diagnostic testing, or even go to see a specialist, however all the results come back “normal”. They are then told “Everything looks fine”.

So what is going on? Obviously things aren’t quite as simple as “Pain 101” would have you believe. Recent research into pain is revealing that the complex interaction between our brain and body is essential to how we process the experience of pain.

Sensations such as smell or sight have specific receptors to detect the stimulus and a direct pathway to the part of the brain that perceives the stimulus. For example, we smell a rose, the receptors in our nose convert the chemical signal into an electrical impulse that goes to our smell center in our brain and we perceive “rose smell”.

Pain on the other hand is perceived when a stimulus gets too intense and passes a “threshold”. It is a warning sign that tissue damage is imminent and we need to stop the stimulus to avoid harm. For example pressure gets too intense, heat gets too hot or even smell gets too strong.

So why do we feel pain in the absence of any obvious tissue injury or after the injury has healed? This can be explained through the process of neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity is the ability of our nervous system to change. Instead of being static, our nervous system is dynamic and adapts to the environment around us and within us.

This means that our nervous system can, in effect, re-wire itself. Lots of things can cause this to happen and in fact it is really happening all the time. For example, when we learn a new skill such as playing the guitar or even learn new tasks as simple as memorizing a phone number our brain makes new connections.

So how does this relate to pain? When pain becomes “persistent” or “chronic” our nervous system can change the threshold at which the “warning signal” of pain is produced. It can be lowered, and in fact, it can become completely disconnected from tissue injury and can be provoked by non- dangerous stimulus such as light touch. In some cases pain can be provoked without any external stimulus at all. Our brain can create pain completely on its own.

A really good example of this is phantom limb pain. Sometimes after a person experiences an amputation of a limb they can still feel pain in that limb even though it is no longer there. If they had a lot of pain in the limb prior to the amputation the chance of getting the “phantom pain” after amputation is increased.

Brain Pain

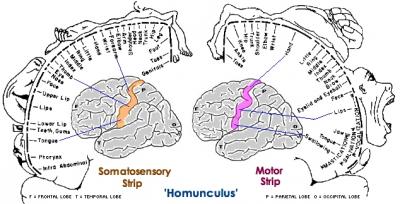

We actually experience pain in our brains not in our limbs. We have a little map in the brain of each part of the body, this is called the Homunculus. When there is pain associated with a certain area of our body the electrical activity in the “brain map” that corresponds to that body part increases. We can have activity in, for example, the left foot part of our brain even if we no longer have a left foot!

This same process keeps our brain sensitized to pain in areas of our body that are not currently injured. Our body is just trying to protect us but the “threat detection” function of our nervous system is on overdrive and perceives threat from sensations that should be perceived as normal.

The protective response includes sending messages to the muscles around area to go into a protective spasm or increase in tone. This hurts! It is like keeping your fist clenched 24/7. So guess what? More pain, and the cycle repeats. It is important to understand that while the problem is not just “in your head” it certainly has been ingrained in your nervous system.

Pain vs Suffering

The distinction between pain and suffering becomes an important one when pain has become persistent. Pain can be considered as a physical sensation and as previously discussed this sensation can be amplified and altered by our nervous system. Suffering on the other hand is the emotional context in which we experience the pain. Our thoughts, fears and beliefs can affect the meaning that we give to our pain.

For many, pain is frightening, and if we have had an experience of trauma this can make the pain more intense. Similarly negative or catastrophizing thoughts about the implications for the future can make dealing with the problem more difficult.

I’ve had many patients express fears for their future if the pain doesn’t get better, how will they cope, what will happen if they can’t work anymore or do the activities that they used to enjoy? This reaction is normal, but when it gets intense or goes on for long time it definitely increases the feeling of suffering that the person with pain experiences.

This can lead to an individual becoming depressed and anxious, their life has been severely altered and restricted. However, this is a reaction to the pain not the cause and it is important to deal with these feelings with a qualified psychological therapist.

Getting Help

Treating persistent pain effectively involves a team approach including your doctor, physiotherapist, other health practioners and psychologist/psychological counsellor.

A physiotherapist who treats persistent or chronic pain will do a thorough examination including a biomechanical and musculoskeletal assessment. A treatment plan will include hands on manual therapy and exercise where appropriate as well as a progressive program of nervous system desensitization. Included in this is physical desensitization of the painful area to teach the body that pressure is just pressure not pain. As well, guided relaxation, deep breathing and mindfulness techniques help tone down the threat response of the nervous system.

While learning to manage pain takes time, with persistence and patience you can change your nervous system to be less reactive. This is the beauty of neuroplasticity. Our brain and nervous system is capable of re-wiring back to a normal response instead of the hyper-vigilant protective reaction that has been in place and is no longer helpful. We have the ability to heal ourselves given the right information and guidance.

If you are interested in learning more about the nervous system and pain a great place to start is with the book “Explain Pain” by Lorimer Mosley. The website http://www.noigroup.com/ has updates on all the recent research going on related to pain, the nervous system, and how to treat/manage pain.